Listed by Month - Category - Title:

February 2014 Posts:

UPDATE/Death Valley - Death Valley National Park

Death Valley - Billie Mine (Death Valley)

Death Valley - 20 Mule Team Road

Death Valley - Borax Mining at Death Valley

Death Valley - Ryan Camp (Lila C Mine) - Death Valley California

Corn Creek - Corn Creek Station (DNWR) - Trip Notes for 02/22/2014

UPDATE - Aztec Tank and Contact Mine

Goodsprings - Aztec Tank - Trip Notes for 02-20-2014

Searchlight - Searchlight Nevada - A Living Ghost Town

UPDATE - Desert National Wildlife Range

Desert National Wildlife Range - Fossil Ridge (North End) - DNWR

UPDATE - Daytrip - Corn Creek Station (DNWR)

Corn Creek/DNWR - Corn Creek Station (DNWR)

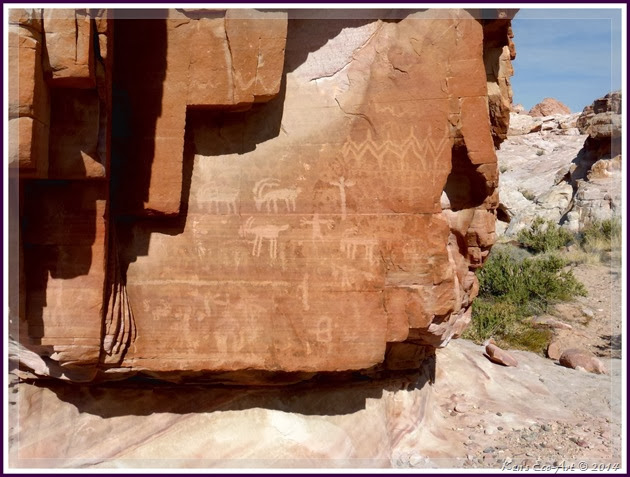

Petroglyphs/Valley of Fire - Mouse's Tank Petroglyphs (Valley of Fire)

Petroglyphs/Valley of Fire - Atlatl Rock Petroglyphs (Valley of Fire)

UPDATE - Furnace Creek Area (Death Valley National Park)

Death Valley - Golden Canyon (Death Valley)

Death Valley - Badwater Basin (Death Valley)

Gold Butte - Little Finland (Gold Butte)

Gold Butte - Black Butte Dam (Gold Butte)

Gold Butte - Falling Man Site (Gold Butte)

Gold Butte - Gold Butte Back Country Byway

Red Rock Canyon - Blue Diamond Trails Hike

Valley of Fire -Silica Dome

Friday

Saturday

Daytrip – Aztec Tank

Aztec Tank is a deep wash at the south eastern foot of the Mount Potosi Range, located about 10 miles behind the town of Goodsprings Nevada. It is reached by following Pauline Mine Road which runs parallel to a large red sandstone outcrop located at the end of the Goodsprings Bypass Road. Using the beginning of Pauline Mine Road as a trailhead, the hike to Aztec Tank is a steady, uphill, two mile hike to Aztec Tank. From the trailhead to the quarry at the top of Aztec Tank Road is a 750 foot elevation gain. Click here for pictures and information on this hike … Aztec Tank - Trip Notes for 02/20/2014. Aztec Tank is a deep wash at the south eastern foot of the Mount Potosi Range, located about 10 miles behind the town of Goodsprings Nevada. It is reached by following Pauline Mine Road which runs parallel to a large red sandstone outcrop located at the end of the Goodsprings Bypass Road. Using the beginning of Pauline Mine Road as a trailhead, the hike to Aztec Tank is a steady, uphill, two mile hike to Aztec Tank. From the trailhead to the quarry at the top of Aztec Tank Road is a 750 foot elevation gain. Click here for pictures and information on this hike … Aztec Tank - Trip Notes for 02/20/2014. |

Daytrip –Desert National Wildlife Range

Today I visited the Corn Creek Station and hiked Fossil Ridge, a roughly four mile long ridge that boarders north side of Gass Peak Road. Though I didn’t have enough time to reach the top, it is rumored to have numerous Gastropod fossils along the top of the ridgeline. Click here for pictures and info … Fossil Ridge (North End). Corn Creek has a brand new 11,000 square foot visitor center that houses exhibits, a gift shop/bookstore, classrooms, and administrative offices for staff personnel. Click here for pictures and info … Corn Creek Station (DNWR). Today I visited the Corn Creek Station and hiked Fossil Ridge, a roughly four mile long ridge that boarders north side of Gass Peak Road. Though I didn’t have enough time to reach the top, it is rumored to have numerous Gastropod fossils along the top of the ridgeline. Click here for pictures and info … Fossil Ridge (North End). Corn Creek has a brand new 11,000 square foot visitor center that houses exhibits, a gift shop/bookstore, classrooms, and administrative offices for staff personnel. Click here for pictures and info … Corn Creek Station (DNWR). |

Sunday

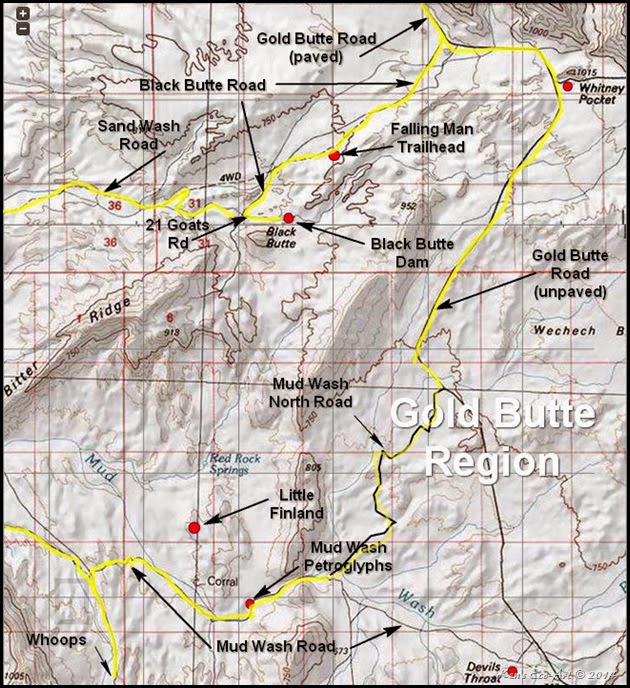

Daytrips – Gold Butte Backcountry Byway & Blue Diamond Hills

Last week I took two hikes, one to the Gold Butte Region and the second to Blue Diamond Hills. The Gold Butte Backcountry Byway is a 62-mile scenic drive that starts at exit 112 on the I-15, just south of Mesquite, Nevada, and heads south into the wild and rugged Gold Butte Region. The Gold Butte Region is administered by the BLM and the U.S. National Park Service. Rich in history, there are several sites of interest that are definitely worth exploring. They are: Falling Man Site, Black Butte Dam, Whitney Pockets, Little Finland, Devils Throat, and the Gold Butte Town Site. Click here for pictures and descriptions of this desolate area … Gold Butte Back Country Byway. Last week I took two hikes, one to the Gold Butte Region and the second to Blue Diamond Hills. The Gold Butte Backcountry Byway is a 62-mile scenic drive that starts at exit 112 on the I-15, just south of Mesquite, Nevada, and heads south into the wild and rugged Gold Butte Region. The Gold Butte Region is administered by the BLM and the U.S. National Park Service. Rich in history, there are several sites of interest that are definitely worth exploring. They are: Falling Man Site, Black Butte Dam, Whitney Pockets, Little Finland, Devils Throat, and the Gold Butte Town Site. Click here for pictures and descriptions of this desolate area … Gold Butte Back Country Byway.  The second hike to the Muffin Rocks at the Cowboy Trail Rides in the Blue Diamond Hills. This steep, 3.62 mile R/T hike had an elevation gain of 815 feet from the trailhead. These rocks are large boulders of conglomerate rock -- much the same as the conglomerate rock layer that underlies the red-and-white sandstone cliffs to the west. However, here atop Blue Diamond Hill, all of the sandstone has eroded away. Click here for pictures and description of this hike … Blue Diamond Trails (Muffin Rocks Trail. The second hike to the Muffin Rocks at the Cowboy Trail Rides in the Blue Diamond Hills. This steep, 3.62 mile R/T hike had an elevation gain of 815 feet from the trailhead. These rocks are large boulders of conglomerate rock -- much the same as the conglomerate rock layer that underlies the red-and-white sandstone cliffs to the west. However, here atop Blue Diamond Hill, all of the sandstone has eroded away. Click here for pictures and description of this hike … Blue Diamond Trails (Muffin Rocks Trail. |

Monday

Category Description

Tabletop Rock Art: I had a real hard time trying to come up with a category name to classify these works and I am still not sure if I like it. I went from 'rock paperweights' to 'rock still life's' to 'tabletop rock art'. Still life art can be any commonplace inanimate object that is purposefully arranged to emphasize texture, color, and composition. Having little to no knowledge about rocks in general, I just began picking up a variety of specimens during my weekly hikes whose characteristics (unique shapes, colors and textures) appealed to me ...

Sunday

Daytrip – Valley of Fire

On yet another visit to Valley of Fire State Park with the rock-hounds from the Henderson Senior Facility, Harvey Smith, Robert Croke and I decided to hike the Silica Dome/Fire Canyon at the end of Rainbow Vista Road. Even though it was kind of an overcast day, we were still able to capture a few nice photos of the rather strenuous two mile R/T hike that involved some class 3 scrambling down into Fire Canyon. Check it out here …Valley of Fire - Trip Notes for 01/30/2014 Silica Dome Hike. On yet another visit to Valley of Fire State Park with the rock-hounds from the Henderson Senior Facility, Harvey Smith, Robert Croke and I decided to hike the Silica Dome/Fire Canyon at the end of Rainbow Vista Road. Even though it was kind of an overcast day, we were still able to capture a few nice photos of the rather strenuous two mile R/T hike that involved some class 3 scrambling down into Fire Canyon. Check it out here …Valley of Fire - Trip Notes for 01/30/2014 Silica Dome Hike. |

Daytrip – Death Valley National Park

I recently made a daytrip to Death Valley National Park with my friend Jim Herring. Although I have stopped at most of these places on previous visits to the park, we decided to make Dante’s View our first stop of the day, a place I had yet to visit. All I can say is WOW. The 13-mile drive to this location provides the best view of Death Valley, bar none. I can’t believe that this was my fourth visit to Death Valley and the first time I had ever been to this outstanding location. Check it out here … Dante's View. I recently made a daytrip to Death Valley National Park with my friend Jim Herring. Although I have stopped at most of these places on previous visits to the park, we decided to make Dante’s View our first stop of the day, a place I had yet to visit. All I can say is WOW. The 13-mile drive to this location provides the best view of Death Valley, bar none. I can’t believe that this was my fourth visit to Death Valley and the first time I had ever been to this outstanding location. Check it out here … Dante's View. |

|

Saturday

Twenty Mule Team Road - Death Valley National Park

{Click on an image to enlarge, then use the back button to return to this page}

This page last updated on 02097/2018

| ||||

| ||||

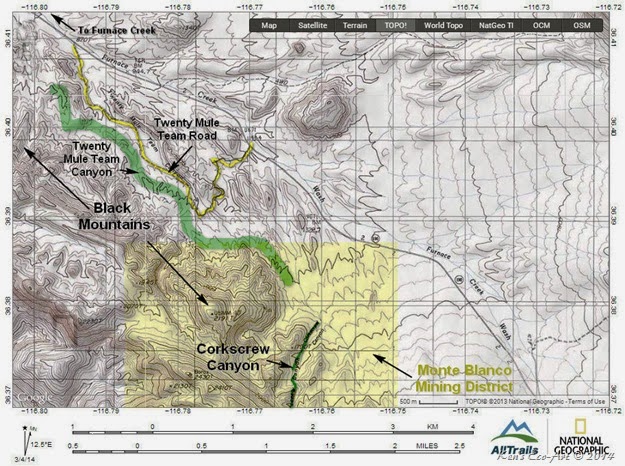

| 02/28/2014 Trip Notes: On today’s visit to Death Valley, we decided to take the short drive onto the Twenty Mule Team Road that takes you into the ‘badlands’ of the Monte Blanco mining district on the northern end of the Black Mountains. This short diversion, though never actually part of the original 165 mile twenty-mule-team Borax freight route used by The Twenty Mule Team Wagons(1) to haul borax out of Death Valley, provided some very interesting and unique geology. You can actually see bands of borax running through some of the mountainous areas surrounding the road. We also saw several foot trails leading into the mountain from some of the small turn-offs along the road, but decided not to stop and explore on today's visit due to the impending rains. | ||||

| Twenty Mule Team Road Description: Created by the remarkable effects of wind, rain and erosion, this scenic drive through multicolored badlands, situated in the old Monte Blanco mining district, provides views of the stunning topography of Twenty Mule Team Canyon in Death Valley. A one-way, single lane road through the northern end of the Black Mountains, it goes through the Death Valley badlands area; an area of quickly eroding, soft mud mountains which were actually once the bottom of a seasonal lake that existed a long, long time ago (before the mountains were uplifted). In the late 1800s, the borax mining industry in the Death Valley area was booming; although Though the Monte Blanco area was ever mined to its full potential, possibly due to the difficulty of reaching the site. There are a couple of small turnouts along the road that allow you to park and hike to the top of its tall mudstone hills and several mine adits. These provide wonderful views of Zabriskie Point and the rich mineral deposits visible within the sedimentary ledges of the surrounding buttes. Traces of mining activity can still be seen in the adits and dugouts that dot the surrounding landscape. The old Monte Blanco mining office and bunkhouse was located near the southern end of Twenty Mule Team Road - in 1954 the building was moved to Furnace Creek where it now houses the Borax Museum. Click here for pictures and info on the museum ... Borax Museum at Furnace Creek Ranch. | ||||

| Borax: Borax has a wide variety of uses. It is a component of many detergents, cosmetics, enamel glazes, insecticides, fire retardants, and more. Borax found in nature is an evaporite, meaning it crystallizes after evaporation of the solute it was dissolved in, in this case, after the seasonal lake dried up (multiple times over and over again in the past). Many deposits were created like this on the muddy bottom of the ancient seasonal lake. In modern day, the ancient lake bottom has been pushed up by tectonic processes and forms the soft muddy mountains, some of which have massive borax deposits mixed in the mud. Its really a neat thing to see, because the borax looks like a bunch of bright white streaks, like powdered sugar or something was sprinkled over and within the mountain. Click here for more information on Borax … Borax. | ||||

| Mining the Borax: The way they did it was kind of interesting. Because a lot of the borax was interspersed with dried mud deposits, the miners had to come up with a process to remove the mud. First, they would dig out a bunch of the borax and mud mix, and together, they then hauled it to a processing facility near present day Furnace Creek. There they dumped it into huge pools or tanks of water where they let the borax dissolve and the dirt settle to the bottom. They did this many times to purify the water, so that only the salts and borax were dissolved in it, and not the unwanted dirt. Then they used the knowledge that borax crystallizes at a certain temperature, so they put a bunch of rods into the tanks and cooled the water down. When the water hit the correct temperature, the rods would act as surfaces which allowed borax crystals to grow on them, and this is the way they were able to extract pure borax from the water. When the Harmony Borax Works was in full swing, it employed 40 men who produced three tons of borax daily! In the heat of the summer, when the water couldn't be cooled to a low enough temperature, they moved the operation to a cooler location, near Tecopa, CA instead of Furnace Creek. Click here for more information on Borax and Borax mining that took place at Death Valley … Borax Mining at Death Valley. | ||||

Ten wagons were built by J.W.S. Perry in Mojave at a cost of $900 each. The wagons' design balanced strength and capacity to cary the heavy loads of borax ore. The rear wheels were 7 feet high, the front wheels 5 feet high (Fig. 03). Each wheel had a steel tire 8 inches wide and an inch thick. The hubs were 18 inches in diameter and 22 inches long. The spokes were of split oak, the axle-trees were solid steel bars. The wagon beds were 16 feet long and 6 feet deep, and could carry 10 tons of borax. Fully loaded (Fig.04), the wagons, including the water tank, weighed 36.5 tons.

When borax was discovered in the Calico Mountains early in the 1890’s, twenty mule teams hauled the ore from Borate to the railroad at Daggett. Except for the brief interlude when the traction engine “Old Dinah” attempted the job, borax was carried solely by these teams until the Borate & Daggett Railroad was built around 1895. Among those who helped make the teams famous were J.W.S. Perry, PCB superintendent, who organized the first teams and mapped the routes; William Delameter, who constructed the wagons; Ed Stiles, driver of the first team; and teamsters Frank Tilton, Johnny O’Keefe, and “Borax Bill” Parkinson. | ||||

Daytrip – Container Park, Strip & Stratosphere

This past week, my friend Jim Herring was in town visiting from Kansas. We spent a day checking out the area surrounding the new Ferris Wheel (not open yet) across from Caesars, the downtown Container Park, a retail and entertainment center partially built with recycled shipping containers that is located a block west at 6th Street and Carson Avenue, only three blocks from the glitz of Las Vegas’ Fremont Street casino corridor. Click here for pictures and info on the Container Park … Container Park. We ended the day with a visit to the 107 Lounge at the top of the Stratosphere Casino for there famous happy hour. With a view to die for, 2-1 drinks and martinis and 1/2 price appetizers, it is one of the best deals in town. Check it out here … The Level 107 Lounge at Stratosphere. This past week, my friend Jim Herring was in town visiting from Kansas. We spent a day checking out the area surrounding the new Ferris Wheel (not open yet) across from Caesars, the downtown Container Park, a retail and entertainment center partially built with recycled shipping containers that is located a block west at 6th Street and Carson Avenue, only three blocks from the glitz of Las Vegas’ Fremont Street casino corridor. Click here for pictures and info on the Container Park … Container Park. We ended the day with a visit to the 107 Lounge at the top of the Stratosphere Casino for there famous happy hour. With a view to die for, 2-1 drinks and martinis and 1/2 price appetizers, it is one of the best deals in town. Check it out here … The Level 107 Lounge at Stratosphere. |

Borax Mining at Death Valley

{Click on an image to enlarge, then use the back button to return to this page}

This page last updated on 02097/2018

| ||

| Borax: Borax, a.k.a.sodium borate, sodium tetraborate, or disodium tetraborate, is a very important boron compound. It a mineral and a salt of boric acid and a soft colorless crystal that dissolves easily in water. Originally imported to the United States from Tibet and Italy, Borax has been used for centuries in ceramics and goldsmithing. A physician is credited with first discovering borax crystals in Northern California while testing waters for medicinal properties. However, it wasn't until "cottonball" [a.k.a. ulexite] — a crude ore compound of boron, oxygen, sodium and calcium — was discovered in large quantities that the domestic industry sprang to life. Cottonball lay in shimmering masses on the ancient desert floor and could be harvested with a shovel. The challenge lay in transporting the ore out of the desolate wasteland for processing into a growing array of industrial and household uses. Boric acid, borax and other compounds of boron are used in almost every major industry — and the company is working throughout its worldwide facilities to develop new applications and products every day. Just a few of the modern products that depend on borates are: Glass — including fiberglass insulation, Pyrex, optical lenses, laboratory glassware and art glass; Porcelain enamel — that covers stoves, refrigerators, freezers, bath fixtures and cookware; Ceramics — as an important component of the glaze on pottery, chinaware and tiles; Detergents and soaps — to enhance whitening, brightening or bleaching of laundry products and as an ingredient in many hand soap formulas; Aircraft and automobiles — to keep engines running clean, in antifreeze, brake fluid, and to build lightweight, high-strength structural sections in aircraft; Cosmetics and medicines — for face creams, lotions, dusting powders, ointments, hair products, and eye bath solutions; Building materials — to flameproof and protect lumber, gypsum board, particle board and insulation materials and to protect them from termites, rot and fungi; Flame retardants — to control the burning rate of wood, paper, and plastic products and to flameproof mattresses; Electronics — as a treatment to the silicon that runs diodes, semi-conductors, transistors and micro circuitry; and Agriculture — as a soil micro-nutrient to aid in plant growth and yield. Even today, scientists are still finding new uses for the unique element. Click here for more pictures and info ... Borax Museum at Furnace Creek Ranch. History of Borax Mining at Death Valley: Borax changed the history of Death Valley. It brought in an industry; it produced the famous Twenty Mule Teams; and it focused the world’s attention on a great new mineral source, which, unlike the ephemeral gold and silver discoveries, was real. There were no “lost” borax mines. The borax mines of Furnace Creek in the Death Valley region were active for a number of years and were the principal producers of borax in the United States. The deposits in this area are separated into two districts; the Ryan District and the Mt. Blanco District. The Ryan District embraces the Biddy Mine, McCarthy Mine, Widow Mine, Lizzie V Mine, Oakley Mine, Lila C Mine, Played-Out Mine and the Billie Mine. The mines of the Ryan District produced mostly colemanite, often in good crystals. Of the known 100 borate minerals, 25 are found in Death Valley. The collage above (Fig. 01) shows six of the Borax ores found around the mining area of Ryan, UL&UR is Colemanite from Ryan; ML&BR are Veatchite and Colemanite from the Billie Mine; MR&BL are Inyoite and Colemanite from Monte Blanco and Ryan respectively. The primary commercial borate ores were borax, kernite, colemanite and ulexite. The ores mined at Ryan were colemanite and ulexite. |

In 1881 Aaron Winters, a prospector who lived in Ash Meadows with his wife, Rosie, offered a night’s lodging to a stranger, Henry Spiller, who was prospecting through the desert. His hospitality was well rewarded. The stranger spoke of the growing interest in the mineral borax and showed him samples of cottonball. One look told Winters that he saw the same crystals every day, covering acre upon acre of the floor of Death Valley. This form of borax was white crystalline ulexite called “cottonball”, which encrusted the ancient lake bed, Lake Manly. The next morning, as soon as his visitor had left, he rode off to the Valley, scooped up a bagful of cottonball and rode back to Ash Meadows. The stranger had told him about the test for borax: pour alcohol and sulfuric acid over the ore and ignite it. If it burns green, it’s borax. At sundown, Aaron and Rosie tried the test on the bagful of sample: “She burns green, Rosie”, shouted Aaron, “We’re rich, by God!” And they were. Winters sold the Death Valley acres he had quickly acquired to William T. Coleman, a prominent San Francisco financier for $20,000, and ended up receiving credit for discovering borax in Death Valley.

These claims were bought by Coleman in 1883 and patented in 1887. A year later Coleman opened the Harmony Borax Works in Death Valley. Hiring Chinese laborers to scrape cottonball from the ancient lake bed for $1.50 per day, and finding that summer processing in the Valley was indeed impossible, he built the Amargosa Borax Works near Shoshone, where the summers were cooler. The ruined remains of these three early borax plants still stand in the desert. The borax was then hauled to the nearest railroad by the use of Twenty Mule Teams hitched to ponderous wagons. At this time, Coleman was producing about 2 million pounds of borax per year from his Death Valley and Amargosa facilities.

In 1882 the Lee brothers discovered a new borax ore on the south side of Furnace Creek Wash in the area of Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon in Death Valley. This new ore was named “colmanite” in honor of borax developer William T. Coleman. The claim became known as the Lila C Mine named at the time by its owner, William T. Coleman after his daughter, Lila C Coleman. This new quartz-like ore demanded far more complex mining methods than cottonball, but it was far richer in borax. Coleman added these borax deposits to his holdings but he never developed them. His financial troubles in 1888 closed the Harmony Borax Works, and they never reopened. In 1890 Coleman sold his properties to an energetic and successful borax prospector from Teel’s Marsh named Francis Marion “Borax” Smith for $550,000 giving Smith a virtual monopoly on domestic borax production. Smith eventually consolidated these properties with his own to create the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

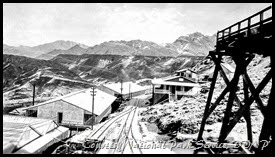

In 1907 Francis “Borax” Smith started mining operations at the Lila C Mine. But the mine was over 120 miles from the nearest railroad. Smith and his business partners decided to build a railroad to service the mine. This new railroad also held the potential to tap in to freighting services in the booming gold and silver mining districts of Goldfield, Tonopah and Bullfrog, Nevada. Smith assigned his top field engineer, John Ryan, to build a railroad to the Lila C Mine. After some initial problems with the original route for the railroad Smith decided to build the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad north from the Santa Fe line at Ludlow, California. Grading began on the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad in 1905 and the line was completed all the way to the Lila C late in 1907. The line ran for 121 miles from Ludlow to Death Valley Junction. Once the railroad reached Death Valley Junction work on the main line stopped and a branch was constructed 7 miles out to the Lila C. After that was completed, work on the main line was continued and the track eventually ran to Beatty, Nevada. The original settlement name of Lila C was changed to Ryan, in honor of John Ryan, Smith’s field engineer. The post office in Ryan opened the same year. This line would ascend around the north end of the Greenwater Range and then they would need to locate a grade through Greenwater Valley to the north end of the Black Mountains of the Funeral Range in order to reach the claims.

The route of the new line went through a group of six borax claims on the west side of the Greenwater Mountains. These claims were located by Coleman’s prospectors in 1883 and 1884 and were called the Played Out, the Biddy McCarthy, the Lower Biddy McCarthy, the Grand View, the Lizzie V. Oakley and the Widow. There was sufficient ore in these claims to sustain production for many years before there would be a need to extend the railroad to the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon claims. This small railroad operated with gasoline engines pulling ore cars that could each carry three tons of ore. The Baby Gauge ore cars brought the borax ore in to Ryan and the small ore cars were pulled up on top of a large wood ore bin into which the ore was dumped. The ore in the large wood bin was then dumped into the narrow gauge hopper cars of the Death Valley Railroad. The DVRR would then haul the ore to Death Valley Junction for processing and final shipment on the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad. While the company was building the railroad to Ryan it moved a processing mill from the Lila C to Death Valley Junction to separate out the borates in low-grade ore. The high-grade ore was shipped by rail to refineries at Alameda, California and Bayonne, New Jersey. The company also built a wet-processing plant and a Stebbins dry-deshaling plant at Ryan to solve ore processing problems.

As the ore at the Lila C began to play out about 1914, plans were already underway to shift operations to reserves further west on the edge of Death Valley. Company engineers had determined that those large deposits would keep the company going for years, while more was always available on the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew claims.

In January, 1915 the Lila C was closed, though not completely abandoned, and the borax activity shifted to the new town of Devair, almost immediately renamed (New) Ryan, on the western edge of the Greenwater Range overlooking Death Valley. According to the original Death Valley Railroad survey, Ryan was to be only the temporary terminus for a line eventually extending down Furnace Creek Wash to the Corkscrew Canyon and Monte Blanco deposits as they were needed. This projected extension never materialized; however, because the Ryan mines -- the Played Out, Upper and Lower Biddy, Grand View, Lizzie V. Oakley, and Widow -- proved even more productive as development increased until 1928. At that time, a deposit of easily accessible rasorite, more economical to mine due to its proximity to the company's new processing plant, was discovered near Kramer (later Boron), California, again precipitating a shift in mining operations. A new calcining plant was built at Death Valley Junction to handle the lower-grade ores coming from the Played Out and Biddy McCarty Mines. When the Death Valley Junction concentrating plant shut down in 1928, a significant era in borax production and processing in the Death Valley region came to an end.

Click here to [Return to the Previous Page]

Ryan Camp (Lila C Mine) - Death Valley National Park

{Click on an image to enlarge, then use the back button to return to this page}

This page last updated on 02097/2018

| ||||

| ||||

| Directions: From the Stratosphere Casino head southwest on S Las Vegas Blvd toward W Baltimore Ave. Travel 1.7 miles and turn right onto Spring Mountain Rd. Go .7 miles and turn left to merge onto I-15 South. Follow for 5.4 miles and take exit 33 to merge onto NV-160 W/Blue Diamond Rd/State Route 160 W toward Pahrump. Continue to follow NV-160 W/State Route 160 West for 55 miles In Pahrump, continue straight on Hwy. 160 through three stoplights then drive 3.1 miles. Turn left at Bell Vista Road and continue 25.5 miles to Death Valley Junction. Turn right and then immediately left on CA Hwy 190 and drive 26 miles and turn left onto Furnace Creek Wash Road. The ghost town of Ryan is about three miles on the left. | ||||

| 02/28/2014 Trip Notes: (planned trip yet to be taken) | ||||

| 01/27/2014 Trip Notes: While driving up Furnace Creek Wash Road to Dante’s View I stopped along the side of the road to take a few pictures of Ryan (Fig. 01) and the dozens of tailing piles that dotted the surrounding hillsides. At the time we had no idea that we were looking at one of the largest Borax mining areas in the state. Currently, I’m planning another trip here at the end of February. | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

History of Ryan: Ryan Company Town is one of the best preserved ghost towns and mining camps in California (Fig. 02). This ghost town epitomizes what the “Old West” was all about. Built in 1914, it was a company mining town built in a remote and rugged area on the side of a steep mountain on the eastern edge of Death Valley National Park that served several borax mines.

| ||||

| ||||

| In 1952 the San Jose State University Field Studies in Natural History started to use the town as their base of operations for their spring time study sessions. Two years later those same students partnered with Ranger L. Floyd Keller in Ryan and created the Death Valley Natural History Association. Over this period Ryan’s founder, Pacific Coast Borax, merged with United States Potash Company, later to become US Borax in 1956. In 1967 US Borax was acquired by the Rio Tinto Group. Sixteen years later in 1983 through 1991 the US Borax exploration department quietly staked mining claims and drilled exploratory holes on the basalt-capped plateau above Ryan. In 1994 Death Valley National Monument became Death Valley National Park. In 2005 Ryan saw its neighbor, the newer and more modern Billie Mine, owned by American Borate Company, shut down operations. Ryan remained quiet a few more years and then Ryan started to catch a lot of people’s attention. The National Park Service started to note in their plans and reports in 2005 that Ryan would make an excellent place for an educational center and expressed desire to partner with Rio Tinto. In 2007 the park service and Rio Tinto started to discuss the idea of Rio Tinto donating Ryan to the park service. In 2008 the Death Valley Conservancy was formed and Rio Tinto decided that the best decision was to donate Ryan to the conservancy. Rio Tinto and the Death Valley Conservancy began the transfer process. In 2012 the San Jose State University Field Studies in Natural History session was not allowed to return to Ryan. Rio Tinto and Death Valley Conservancy propose upgrades to a water collection system at Navel Spring inside Death Valley National Park. And a short time later a Fundraising Agreement is entered into between the National Park Service and Death Valley Conservancy. On May 6, 2013 the Death Valley Conservancy announced the transfer of ownership of Ryan Camp from Rio Tinto to the Death Valley Conservancy. In addition to the land and property, Rio Tinto will contribute $750,000 in financial support to the DVC in the first year, with further support scaling up over time to $18 million. The money will be used to address deferred maintenance and provide an endowment to help keep the site protected into the future. Rio Tinto's financial support will allow the DVC to preserve and restore Ryan Camp, as well as promote research and education centered on historic preservation and archaeology. | ||||

Falling Man Site (Summary Page)

{Click on an image to enlarge, then use the back button to return to this page}

This page last updated on 03/18/2018

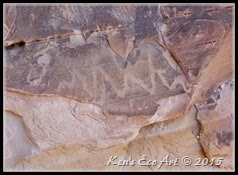

Introduction: As I began to discover more and more rock art sites during my hikes over these past several years, I have become witness to far too many examples of where persons had seemed fit to deface them with graffiti and other examples of damage. Eventually I realized that the sharing of my hiking adventures could have the potential to increase public exposure, and thereby increasing the possibility for even more damage. As a result, I decided to preface each of my rock art pages with the following information to help educate visitors about the importance of these fragile cultural resources. Before scrolling down, I implore you to READ the following ... as well as the linked page providing guidelines for preserving rock art.

Here are a few simple guidelines you can follow that will help to preserve these unique and fragile cultural resources that are part of our heritage. Guidelines for Preserving Rock Art. If you would like to learn more about the Nevada Site Stewardship Program, go to my page ... Nevada Site Stewardship Program (NSSP).

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

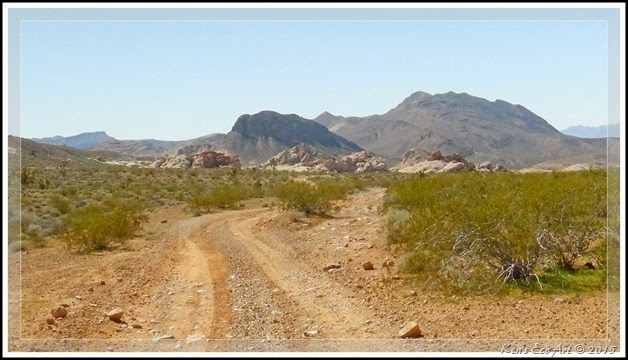

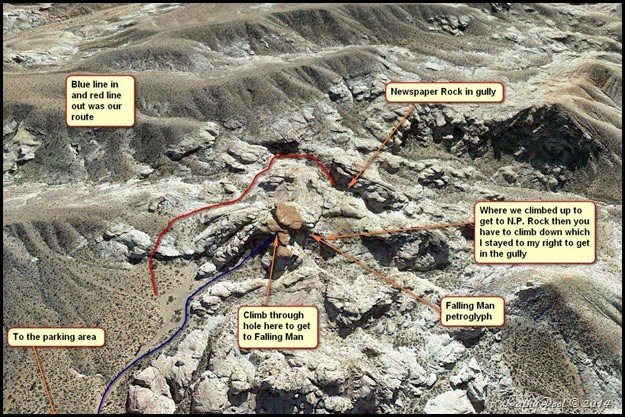

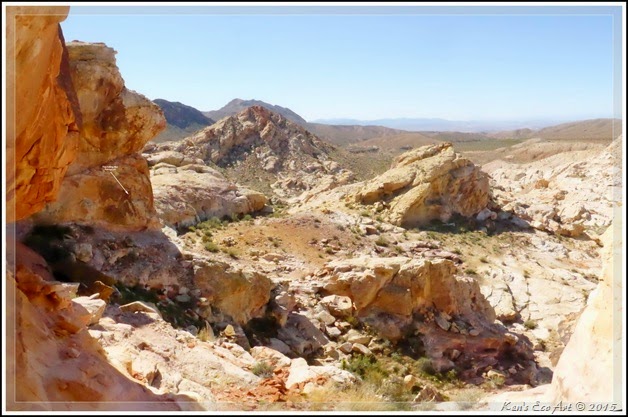

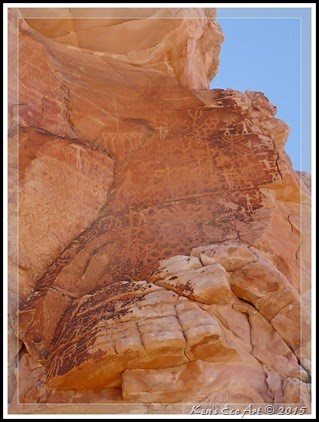

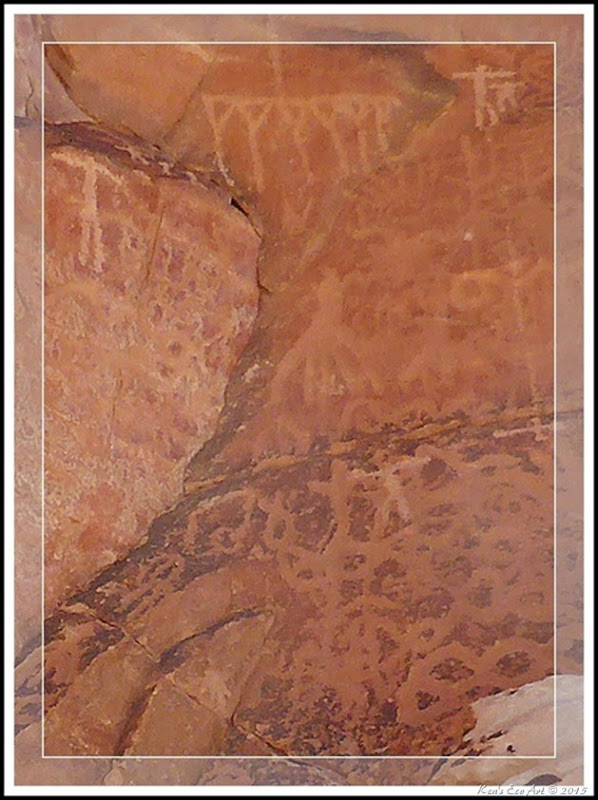

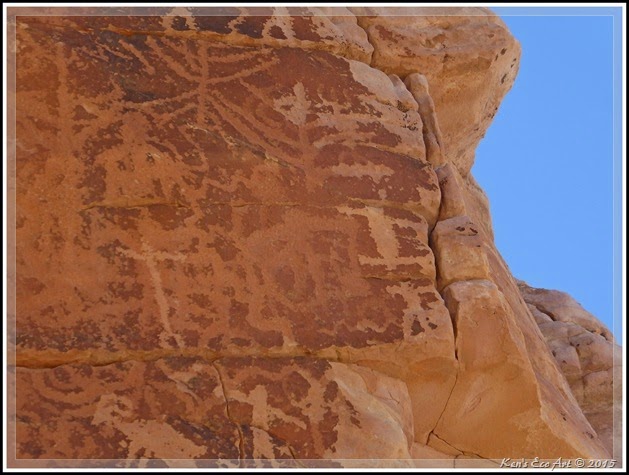

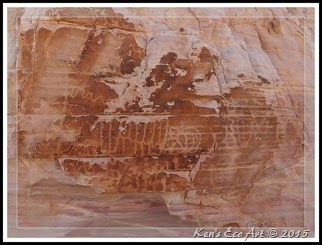

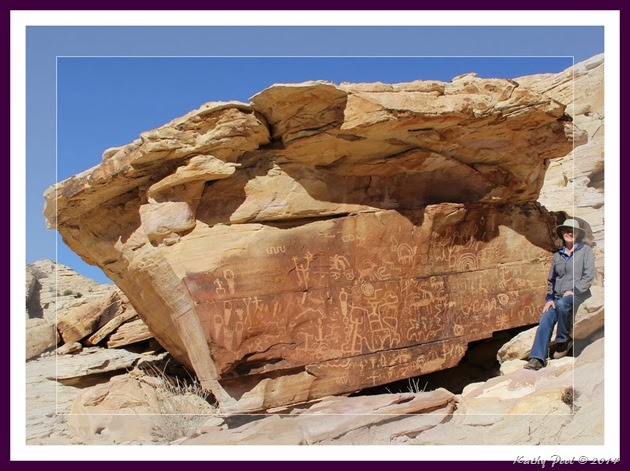

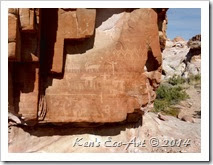

| Site Description: Generally called the “Falling Man” site, this area is sometimes referred to as the “Whitney-Hartman” area, though this term is not used by locals. Located just a few miles down Black Butte Road, off the Gold Butte Back Country Byway, the outcrop of white and orange and red Aztec sandstone crags rising up out of the surrounding desert floor contains dozens of expertly pecked petroglyph panels, some containing more than 100 individual glyphs. Of all the areas I have visited in the Gold Butte Region, I believe this site is the most prolific, containing more panels and glyphs than any other. As you approach the site from the northeast, it is silhouetted against Black Butte Peak and the Bitter Ridge in the background (Fig. 03). At an elevation of 2,420 feet (at the parking area), it is surrounded by what is referred to as Mojave Desert Scrub, a vast and diverse expanse of shrubs, joshua trees, and cactus. | |||||||||

| Who Made Gold Butte’s Rock Art?: It is nearly impossible to find any real specific archeological data relating to who and when various cultures may have lived in or passed through the Gold Butte Region. It appears to be generally believed that Archaic hunter-gathers were the first prehistoric rock art makers to live here. Because this period is generally divided into three time frames: The Early Archaic Period between 7000-4000 BC, when the environment began changing to more arid conditions; The Middle Archaic Period from 4000-1500 BC, when it appears that a wider variety of plants and animals were harvested as natural resources and more intensively exploited as populations increased and seasonal rounds became more territorially established; and lastly, the Late Archaic Period from 1500 BC to the period of contact with Euro-Americans in the nineteenth century, many of the petroglyphs here can be anywhere from 7000 to 700 years old. It appears that at some point the early hunter-gathers were followed by the Virgin Branch of the Keyenta Anasazi which appear to have occupied the area until sometime between 1000-1300 AD. Coming from the east, the western Anasazi include the Kayenta Anasazi of northeastern Arizona and the Virgin Anasazi of southwestern Utah and northwestern Arizona, both areas of which boarder the Gold Butte Region. NOTE: Though the term "Anasazi" is often used to describe various cultures, it is a Navajo term meaning "ancient ones", "ancient ancestors" or "ancient enemy", depending upon interpretation; its neutrality should thus not be blindly assumed. Eventually the Anasazi were replaced by the Southern Paiute. Archaeologists generally agree that, for several centuries, indigenous people - now known as the Southern Paiute Indians - lived in the area that ultimately became Southern Nevada. When one gazes over this arid desert area today, one has to wonder how the Southern Paiutes and their generations of ancestors endured. It is believed that their success was based upon their knowledge of where their water came from. Their water rose up out of the ground as natural springs that were sometimes evident, and sometimes hidden. This knowledge of water locations was transferred between Paiute groups. It has been documented that the location of hidden water was even indicated by petroglyphs carved in stone so that Paiutes, who often on the move to follow their food, could only survive by knowing how to access the underground water. Because the weather differed somewhat every year, the Paiutes often traveled dozens of miles to the most promising food sources, becoming experts at finding the best sources of food and water in an ever-changing arid desert. Still today there are no less than two dozen natural springs located throughout the Gold Butte Region. As westerners began to infiltrate their lands, the Paiutes began to retreat deeper into the more desolate desert areas to avoid them. In spite of this information, so far, none of my research has come up with anything that definitively estimates when some of the various petroglyphs within Gold Butte were created. This is further complicated by the fact that over the years different peoples utilized the resources of Gold Butte making it even more difficult to determine who made what rock art. There is strong evidence that indicates several panels found here include some superimposition of petroglyphs pecked over older images. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

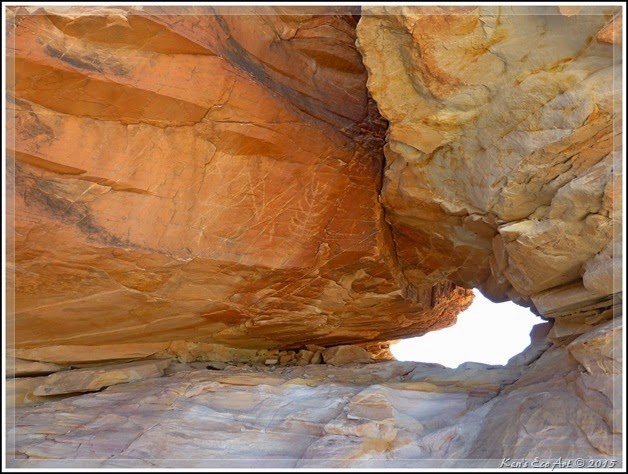

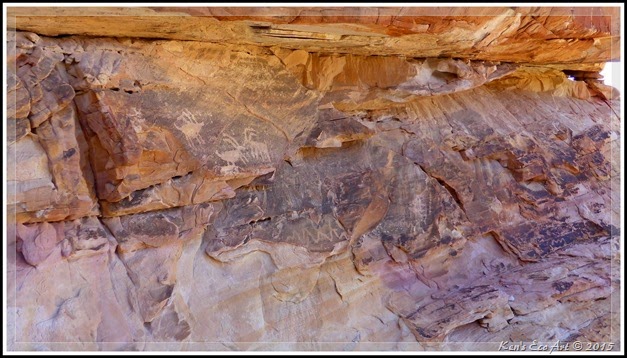

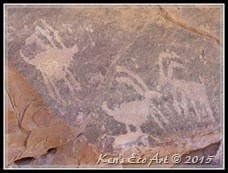

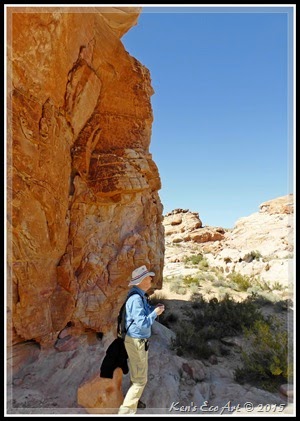

| 10/22/2015 Trip Notes: On this trip to the Falling Man Rock site with the rock-hounds from the Henderson Senior Center, the majority of the hikers visited this site while Blake Smith and I hiked to the dam at Whitney Pocket. Scroll down for pictures from my previous visits. Click here to view the Whitney Pocket and the dam ... Whitney Pocket at Gold Butte National Monument. 03/05/2015 Trip Notes: Today I made another visit to the Falling Man Rock art site (Fig. 03) in Gold Butte with the rock-hounds from the Henderson Senior Center. Unfortunately our van was unable to reach the site due to a wash out on Black Butte Road and ended up getting bogged down in soft sand trying to turn around. After spending nearly two hours trying to get it turned around we finally ended up calling a wrecker from Las Vegas to come and retrieve us. While waiting for the wrecker to come three of us (Robert Croke and Blake Smith and myself - Fig. 04) decided to hike the remaining couple of miles down the road to the site (Fig. 01). The many rocky, sandstone crags that make up this site contain dozens of many fine petroglyphs. The goal of today’s visit, with the aid of the map provided by fellow hiker Kathy Pool (Fig. 05), was to locate “Newspaper Rock” and the “Falling Man” glyph for which the site is named. After Heading south from the parking coral, we followed the trail down the wash until we located the hole in the rocks near the top of the cliffs off to the right (Fig. 06). Notice the ‘tree-like’ glyph just to the left of the opening. To the right of the opening there is a quite large panel (Fig. 07) with several large zoomorphs that appear to be bighorn sheep (Fig. 08), with possibly a ‘snake-like’ glyph in (Fig. 10). Once we crawled through the small opening in the rocks we were presented with the view in (Fig. 11). The arrow in the middle left of this figure shows the location of the “Falling Man” glyph (Fig. 12). Unfortunately, once again, we ran short on time and had to head back before reaching “Newspaper Rock” (Fig. 20). Refer to these figures below for more information about these glyphs. We did however discover another large outcrop with more than forty images (Figs. 13 & 14) that, in addition to some abstract images, contained several zoomorphs and more than a dozen anthropomorphs (human-like figures) (Fig. 15 & 16). The different tones in the color of the desert varnish of the glyphs here suggest that they may have been made by more than one group of inhabitants over a period of many years. Blake discovered several more rather abstract images nearer the ground on the backside of this outcrop (Figs. 17 & 18). (Remember to click on any of these images to enlarge for better viewing) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| The Falling Man glyph: Could this petroglyph represent an actual event, such as a fellow tribesman who fell and lost his life while creating some of the area's spectacular petroglyphs, or could it be a shaman descending to or from the spirit world, or something entirely different. We may never know. I have read that this image can be found in two other different locations; one in Whitney Pockets near Valley of Fire State Park and one in the Grand Canyon National Park. The fact that the images at these three sites are nearly identical seems to suggest the same pre-historic artist created all three images. As their locations are in a reasonable proximity to each other, that possibility is not too far-fetched. It is easy to assume that a shaman could have traveled to the three sites over the course of time, thereby creating each of these images. | |||||||||

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

| (Fig. 19) |

Newspaper Rock: Newspaper rock or "picture rock”, as it is sometimes called because people like to have heir picture taken in front of it (Fig. 20). Some archaeologists believe that this panel has glyphs from three time periods, archaic, anasazi and patayan. The archaic glyphs are the oldest and are typically curvilinear or rectilinear in form; the Anasazi glyphs are identified as people or animals having “full formed” bodies, and the patayan people typically are more “stick” figures with large hands and/or feet. Likewise the animals are more like stick figures. It is also one of the few panels in the area having “burden baskets” which can be found on the left side of the panel. Burden baskets are cone shaped, with flat or rounded bottoms. The baskets were once made for every day use in collecting or gathering wild foods, or to cultivate crops like corn. Large burden baskets were sometimes made for food storage. You will see how the Bat Clan (many, many bat clan symbols in the area) documented the good years (full burden baskets) and the bad years (empty burden baskets) with wonderful petroglyphs. You can visually see their plea to rain god Tulilic, as the Kokopelli lays on his back to play his flute to the sky world.

|

| (Fig. 21) |

|

|

| ||

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)