|

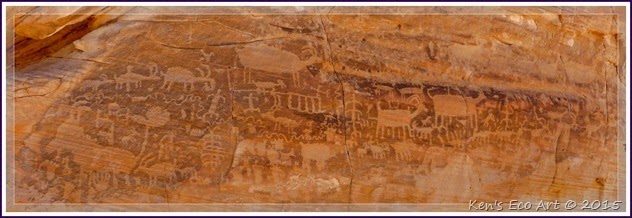

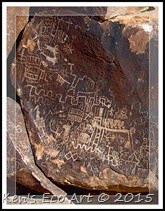

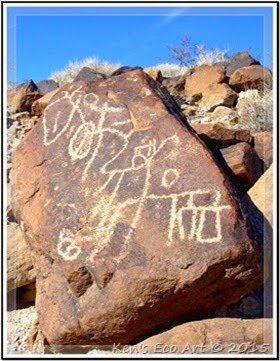

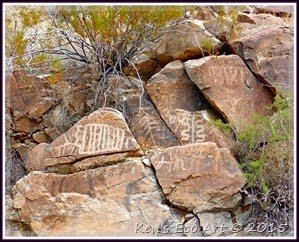

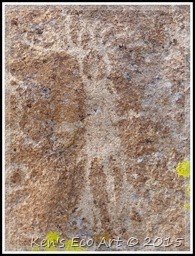

What is Rock Art? There are two basic types of rock art. The first being petroglyphs; motifs that are pecked, ground, incised, abraded, or scratched on a rock surface. The second being pictographs (sometimes called rock paintings); motifs in one or more colors using mineral pigments and plant dyes that have been drawn, daubed, spattered or painted onto the surface of rock found in the walls of caves, canyons, on boulders, in bedrock and sometimes on the floors of caves. Although sometimes images may have originally been executed as a combination of both techniques, most now appear only as a petroglyph because the painted material has faded or washed away over hundreds if not thousands of years.

|

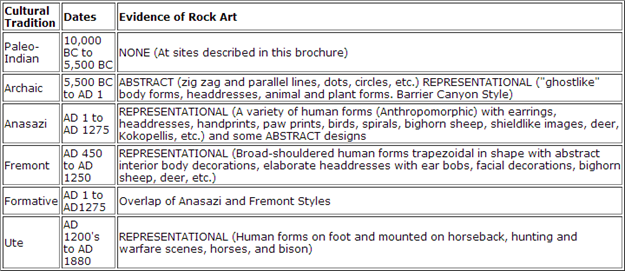

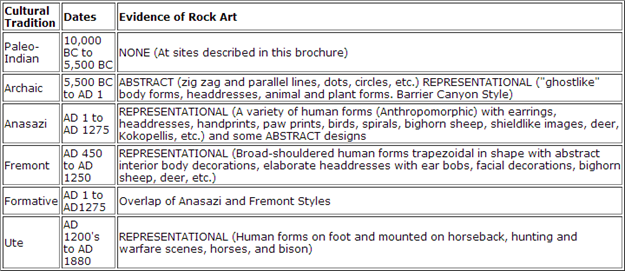

| Dating The People & Cultures: Nevada rock art was produced by a number of prehistoric and historic peoples over thousands of years, making the history of the area very complex. Peoples first entered Nevada and the Great Basin some 12,000 to 10,000 years ago as the Ice Age ended and glaciers across North America finally receded (Fig. 01). Although it is difficult to establish an exact age of rock art, some dating clues are easily identified. For example whenever a horse and rider is depicted, we know the date to be after AD 1540 when the Spaniards reintroduced the horse to the New World. The presence of bows and arrows is presumed to indicate a date after AD 500, the generally accepted time period for their appearance in this region. For identification purposes, the time periods below are broken into generalized categories relating to the people believed to have made them. |

|

| (Fig. 01) |

|

| The Paleoarchaic Period. During this period, between 10000-7000 BC, the region was wetter than today’s climate, with residual Pleistocene lakes, marshes, and wetlands that slowly dried up as the climate changed to a warmer and drier regime. During this time Nevada was only sparsely settled with early hunter-foragers known as Paleo-Indians. They focused on big-game hunting and harvesting the resources of wetlands; settlement appears concentrated on lakes and wetlands. Many parts of the state appear to have only been used for sporadic foraging expeditions and population densities were probably very low. Most archaeological remains are of hunting and foraging sites, and a variety of hunting tools. |

| The Early Archaic Period. During this period, between 7000-4000 BC, the environment began changing to more arid conditions. Many lakeside marshes disappeared and desert shrubs expanded into lower elevations. Settlement became more permanent and repeated throughout the region and economic strategies diversified according to regional environmental variables. During the winter, populations concentrated in valley floors or near permanent water sources. Use of the spear for hunting appears to have been replaced in favor of large dart points hurled from atlatls or spear-throwers. Milling equipment (manos and metates) become more common, indicating that seeds, tubers, and other plants were harvested. |

| The Middle Archaic Period. From 4000-1500 BC, it appears that a wider variety of plants and animals were harvested as natural resources were more intensively exploited as populations increased and seasonal rounds became more territorially established. A wider range of milling tools appears in the archaeological record. Caches of artifacts and other materials indicate that storage at times played an important role in decisions about residential mobility, with preferred places repeatedly revisited. Exchange in marine shell and obsidian becomes evident and mastery of textiles is displayed in surviving baskets and other tools made from cordage. |

| The Late Archaic Period. From 1500 BC to the period of contact with Euro-Americans in the nineteenth century, significant environmental, settlement, and technological changes are witnessed, with regional semi-horticultural economies emerging in eastern and southern Nevada. The climate changed toward much warmer and drier conditions that characterize today’s modern climate. Bow and arrow technology was introduced from the west, evidenced by smaller projectile points. Economic practices relied on hunting small mammals and harvesting plants and seeds; milling equipment becomes more elaborate and more frequent at Late Archaic camp sites. Pottery begins to be made around 900 years ago. |

|

|

| In southern and eastern Nevada, economies with variable reliance on horticulture (maize cultivation) and harvesting wild resources began to develop. The Anasazi, AD 1 to AD 1275, whose culture centered south of Moab in the Four Corners area, eventually spread into the south eastern areas of Nevada mixing with the Freemont, AD 450 to AD 1250, peoples to the east in Utah, marking an Ancestral Puebloan presence. This is evidenced by distinctive pottery, pit-houses, and above ground architecture. These are also characterized by distinctive domestic architecture (pit houses and above ground structures) but harvesting wild resources seems to have played an important role in their economic practices in addition to horticulture. Both the Ancestral Puebloan and Fremont presences in Nevada are associated with distinctive rock art portrayals of the human form. They concentrated much of their subsistence efforts on the cultivation of corn, beans and squash. These sedentary people also harvested a wide variety of wild resources such as pinion nuts, grasses, bighorn sheep and deer. The Fremont, who were contemporary with the Anasazi people, also grew corn and were apparently more dependent on hunting and gathering wild resources than were the Anasazi. Their territory was mainly in the Great Basin north of the Colorado River but overlapped with the Anasazi at Moab. Both cultures had a complex social structure and were highly adaptive to the extremes of the environment. The Anasazi and Fremont are classified by scientists as "Formative" cultures. |

|

|

| Around 700 years ago, the Ancestral Puebloan and Fremont economies are replaced by economies focused on hunter-foraging. Some Great Basin archaeologists have suggested that this is when the ancestors of most modern Indian Peoples, the Utes and Paiutes, AD 1200 to AD 1880, settled Nevada. It is equally possible that changes in material culture recorded in the archaeological record reflect endogenous social and economic changes in response to climatic fluctuations, shifting distributions of animal and plant species, and influences from neighboring cultures. They were a very mobile hunting and gathering people who roamed the Great Basin. They used the bow and arrow, made baskets and brownware pottery, and lived in brush wickiups and tipis. These people lived freely until the late 1880’s when they were forced onto reservations. |

|

|

| Categories of Rock Art: Found on rock surfaces all over the Southwest desert, southwestern rock art generally depicts people, animals and other shapes and forms. It is basically divided into two categories known as representational and abstract. |